Characterising uncertainty for parts of the uncertainty analysis is needed for assessments where the assessors choose to divide the uncertainty analysis into parts, but may only be done for some of the parts, with the other parts being considered when characterising overall uncertainty.

When characterising overall uncertainty assessors should initially include all sources of uncertainty that might be relevant, not only those they are sure are relevant. This is necessary to minimise the risk of overlooking sources of uncertainty which, while initially of doubtful significance, may prove on further analysis to be important.It is recommended to use a systematic approach for identifying uncertainties, to minimise the risk of overlooking important ones.

In many assessments, the number of potentially relevant sources of uncertainty identified may be large. All the sources of uncertainty that are identified must be recorded in a list. This is necessary to inform the assessors’ judgement of the overall uncertainty and ensure a transparent record of the assessment.

With the exception of standardised assessments, assessors should try to quantify the combined impact of as many as possible of the uncertainties on the question or quantity of interest.

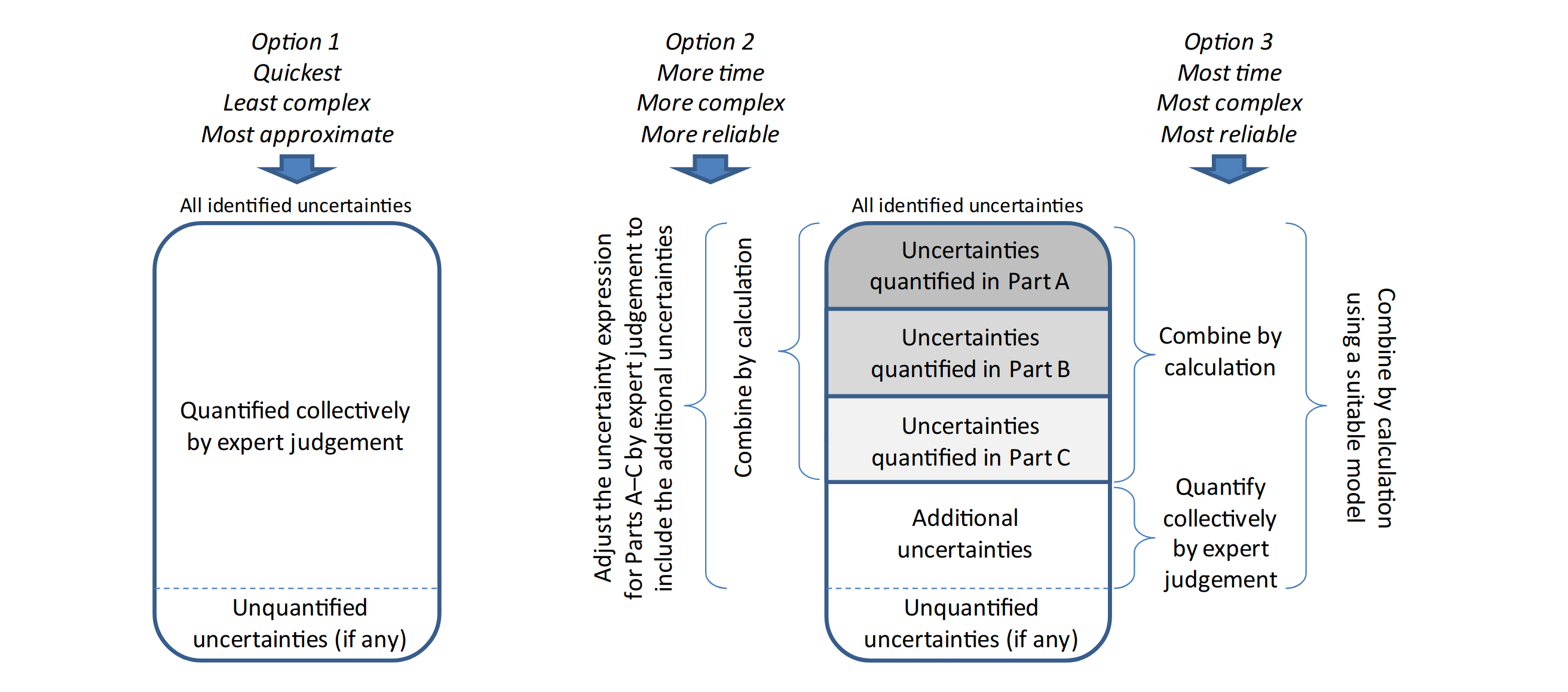

There are three options for quantifying the overall uncertainty, depending on the context:

Make a single judgement of the overall impact of all the identified uncertainties. This is applicable in assessments where the uncertainty analysis has not been divided into parts. Assessors should quantify the collective impact of as many as possible of the identified uncertainties directly by expert judgement, using formal or semi-formal EKE. If assessors find it too challenging to express their judgement of the overall uncertainty as a probability distribution (if continuous quantity of interest) or precise probability (if categorical quantity of interest), it may be sufficient to give an approximate probability.

Quantify uncertainty separately in some parts of the assessment, combine them by calculation, and then adjust the result of the calculation by expert judgement to account for the additional uncertainties that are not yet included.

This is suitable in assessments where the uncertainty analysis has been divided into parts, and the assessors have quantified and combined at least some of the uncertainties in at least some parts of the assessment earlier in the uncertainty analysis.

The task that remains is to characterise the overall uncertainty, including those already quantified and the additional uncertainties that are not yet quantified. Some of the additional uncertainties may be uncertainties that were not included in the parts that were previously quantified, while others may relate to the model used for combining the parts. In this option, the contribution of the additional uncertainties is combined with the previously quantified uncertainties by expert judgement. Expert judgement is simpler, because it does not require explicit specification of a model for combining the uncertainties by calculation, but is more approximate because the combination must be done by subjective judgement.

Quantify uncertainty separately in some parts of the assessment and combine them by calculation. Then quantify the contribution of the additional uncertainties separately, by expert judgement, and combine it with the previously quantified uncertainty by calculation.

This option involves judging the impact of the additional uncertainties as an additive or multiplicative factor on the scale of the quantity being assessed, expressed as a distribution or probability bound, and then combining this by calculation with the quantitative expression for uncertainties that were quantified and combined earlier in the assessment.

This is analogous to the well-established practice of using additional assessment factors to allow for additional sources of uncertainty. For example, EFSA endorses the use of case-by-case expert judgement to assign additional assessment factors to address uncertainties due to deficiencies in available data, extrapolation for duration of exposure, extrapolation from lowest observed adverse effect level (LOAEL) to no observed adverse effect level (NOAEL) and extrapolation from severe to less severe effects. However, the approach proposed here is more rigorous and transparent because it makes explicit the probability judgements that are implied when using such assessment factors.

This option seems less useful when the subject of assessment is a yes/no question. This is because it seems likely that experts would find it easiest to judge the necessary adjustment by thinking first about what the calculated probability needs to be adjusted to and then back-calculating, so there is no advantage over eliciting the adjusted probability directly.

In some assessments, there may be some identified sources of uncertainty that the assessors are unable to include in their quantitative expression of overall uncertainty. When this happens, the unquantified uncertainties must be characterised qualitatively and reported alongside the quantitative expression of uncertainty. The quantitative expression will then be conditional on the assumptions that have been made about these unquantified uncertainties. This has major implications for decision-making, so assessors should try to include as many uncertainties as possible in their quantitative expression.